The Middle Ages in France was a time of almost fanatical religious belief, when the Catholic Church held great power. Indeed, the dominant aspect of culture was the Christian faith. Since the manner in which a society spends its wealth expresses its values, it is not surprising that art in the Middle Ages was permeated by religious themes. This is evident in manuscript illumination, cathedral architecture, sculpture, and tapestries, much of which were commissioned for or by the Church.

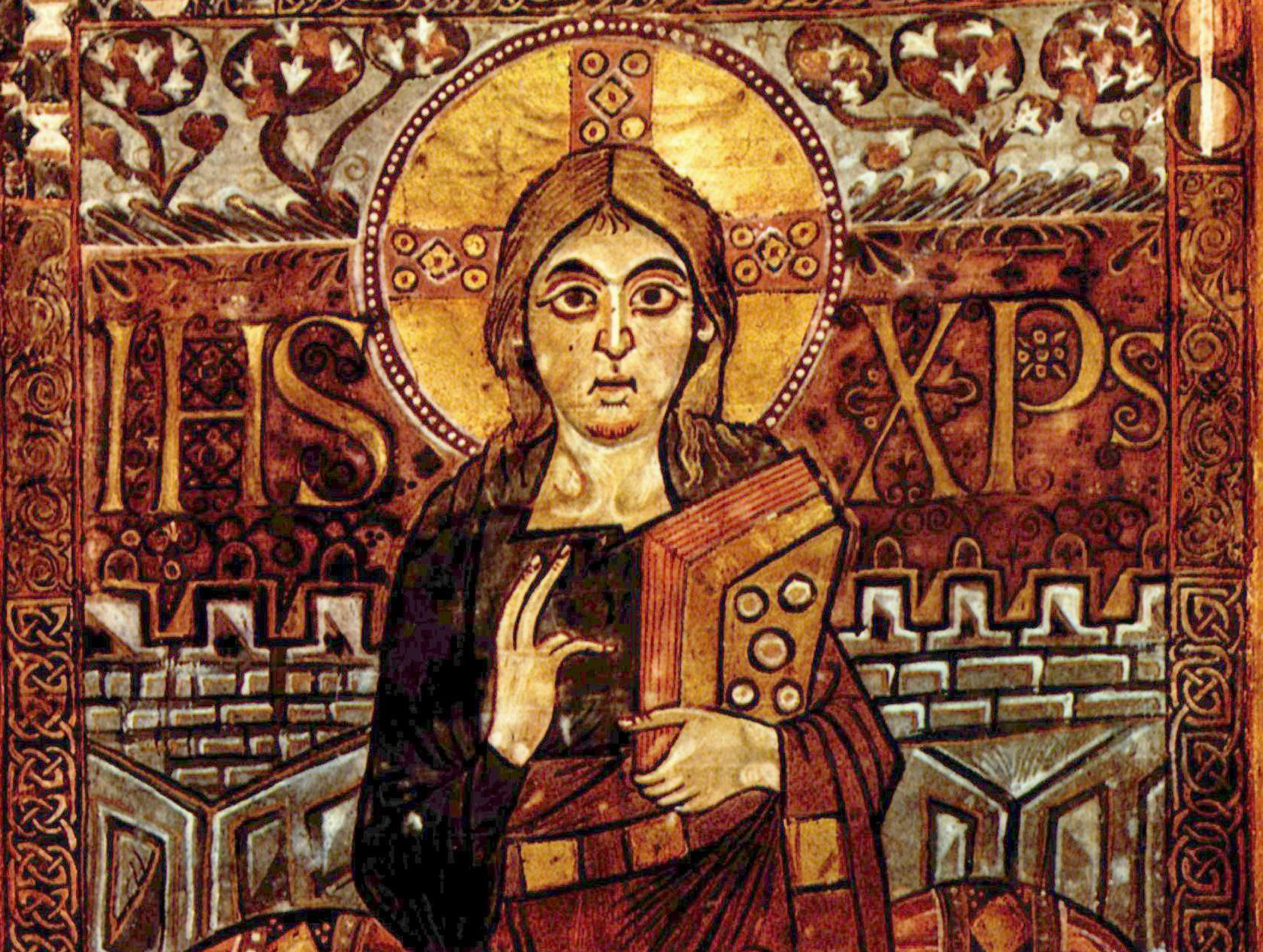

The predominant type of painting in the early Middle Ages was the decoration of bibles. This manuscript illumination was brought to France by Charlemagne as part of his attempt to renew the state of Classical culture which existed in the Late Antique period in Rome. To achieve this, Charlemagne imported scholars, artists and other knowledgeable people to his court at Aachen. These people promoted the learning that was essential to Charlemagne’s plan of a cultured nation. The copying of bible books, borrowed from Rome, was paramount to attaining this goal.

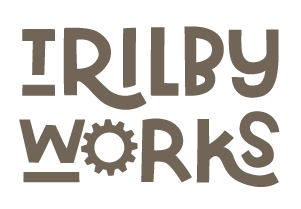

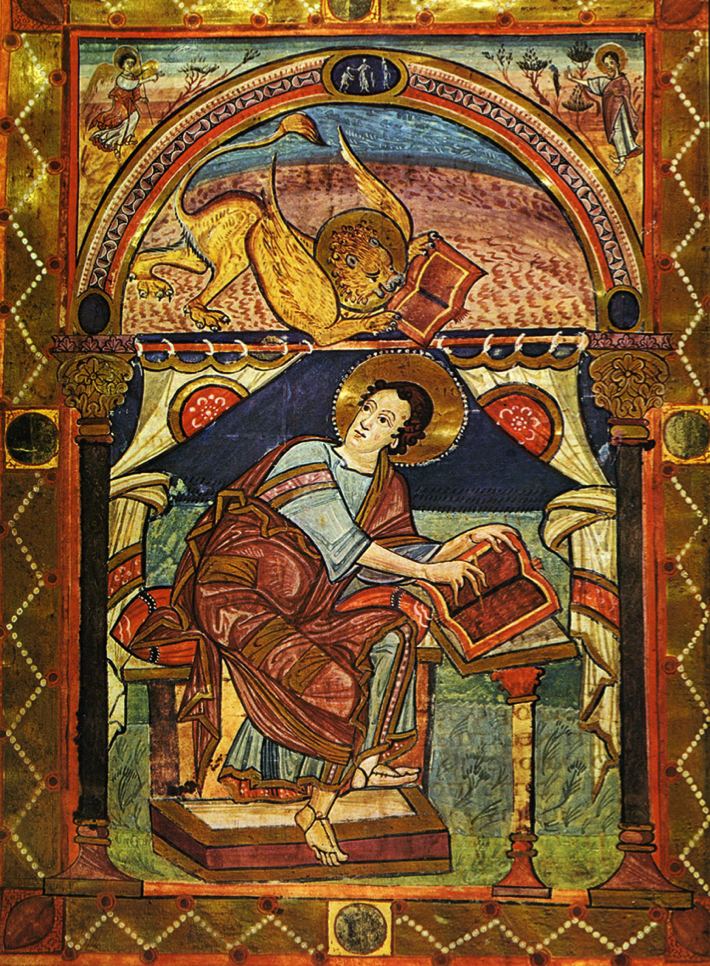

The eminent illuminated manuscript produced during the reign of Charlemagne (768-814) was the Godescalc Evangelistary. But the portrait of Christ, instead of evoking Roman art, combined several existing artistic styles. Some Classical elements may be seen, such as the architecture, the Roman-looking robe, and the sandals. However, the halo, the large eyes, the crushed flat drapery with abstract folds, and the three-dot pattern of the material show a Byzantine influence. Unfortunately, the most evident influence is the Barbarian one, that is, the inability to draw realistic, lifelike figures. Problems with body proportion are obvious in the posture of Christ. He appears to be sitting but the supporting cushion cuts through his back. The remaining space is filled with interlacing and abstract designs done in rich colors.

In short, Charlemagne’s attempt at recreating Classical civilization failed, at least in terms of manuscript illumination: his artists forged ahead, creating a unique style. And alas, illuminated manuscripts were eventually replaced by stained glass as the foremost medium of artistic expression. This reflected a shift to a public focus for art.

One type of artistic expression that was more permanent, although the style changed radically, was the cathedral. This monumental structure was an important addition to a town, because it contained the seat of the bishop, thus conferring great status upon the town. In an age when the King of France had little authority over the independently governed provinces, the people looked to the Church for stability and guidance. Thus, a cathedral was an indication of the wealth and prominence of one’s town. In addition, the soaring edifice was a source of immense civic pride.

Consequently, an increase in building activity of churches in the eleventh century signaled the beginning of the Romanesque period of architecture, so called because the rectangular shape and exterior sculpture were reminiscent of Classical Roman buildings. This Romanesque look is characterized by thick walls, heavy buttresses, tiny arches, few windows, square towers, and barrel vaulting. The church of St. Philibert’s at Tournus (early eleventh century), with its severe dignity, was typical of this style of church architecture.

As Christian fervor continued to permeate the culture of the French people, ideas emerged to glorify the church even more. Thus, the Romanesque style soon became obsolete as it gave way to a glorious new style which later art historians call Gothic. The Gothic style of architecture evolved largely because of the vision and efforts of Abbot Suger who began creating his Abbey Church at St. Denis in 1135. His cathedral possessed pointed arches, flying buttresses, many stained glass windows, and a lacy, graceful exterior. This new style of architecture, with its high ceilings, was the perfect showcase for stained glass, since the dark, cavernous space cried out for light. Abbot Suger’s goal was to transform the interior of the church into a heaven-like area. Only stained glass windows could create this effect. Light filtered through, creating pools of bright colors, which changed depending upon the time of day. The effect was designed to awe the worshipper, to make him believe in the glory of God. Thus the Church gained an element of control over the people.

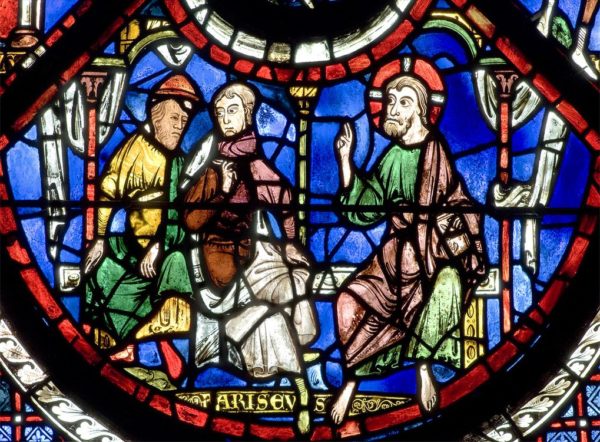

Stained glass windows served to educate the illiterate masses in the stories of the Bible. In the Cathedral of Chartres we find depictions of Mary, Jesus, and the Apostles.

In the second half of the eleventh century, there developed a new interest in the Virgin Mary. Stories of her miracles were collected, churches were dedicated in her name, and increasing numbers of images were created of her. The Virgin Mary was considered wise, humble, pure and tender. These qualities were possessed by ordinary women, but in Mary they embodied the ultimate perfection. This interest in Mary is thought to reflect an emerging appreciation for women in general.

This worship of the Virgin Mary is manifest in the large number of wooden statues which were created at the time. “The Virgin and Child Enthroned,” from the Auvergne region of France, late twelfth century, exemplifies this trend. The two-foot high sculpture is rigidly frontal, and displays the typical Medieval problems with proportion. The Virgin’s upper body is much longer than her lower body, because her legs from knees to hips are too short. However, the real problem is the Christ Child who has not the plump, rounded body of a baby, but that of a fully grown, albeit tiny, man. He sits stiffly upright on the Virgin’s lap, not a very baby-like position, with his right hand raised in the priestly gesture of blessing and his left resting on an open book, symbolizing his divine wisdom. The Virgin is seated on a four-legged stool, rather than a throne, indicating her humility.

Tapestry making flourished in the Middle Ages. The wool tapestries were first woven in monasteries and convents as wall hangings for churches. Few of these early tapestries, which depicted religious scenes, exist today. Nobles liked the heavy, portable tapestries and used them to create a warm atmosphere in their living quarters. As society became more secularized in the later fourteenth century, perhaps due to the emerging middle class, tapestries began to depict non-religious scenes such as the “Nine Heroes” tapestry. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters, New York).

In summary, Medieval artists translated their religious energy to art. Their art was not an end in itself, but also a tool used by the ruling classes to create objects of worship and to educate the common people.

Bibliography

- Gold, Penny Schine. The Lady and the Virgin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Stokstad, Marilyn. Medieval Art. New York: Harper and Row, 1986.

- Young, Bonnie. A Walk Through the Cloisters. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.

- Carolingian Painting. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.

- Burke, John. Life in the Castle in Medieval England. New York: British Heritage Press, 1978.